Molly Valentine Dierks

- Anna Lilli Garai

- Aug 12

- 9 min read

Molly Valentine Dierks works with sculpture and installation, using found materials, textures, and language. She brings together objects from nature, industry, and daily life, based on how they feel or what they suggest. Her works often reflect ideas around care, time, and change. In pieces like “Day Labor (…to Love One Another)” and “Cloud Transmission (to hold and to let go…)” she combines raw elements with quieter, more personal details. Her process is shaped by movement, memory, and what she notices in her surroundings.

Q: “Day Labor (…to Love One Another)” comes from Rilke and speaks to invisible care. Why did rebar and labor feel like the right way to show that?

A: The idea came about organically, as I was wandering around the back of my apartment complex as the pandemic was first unfolding. A construction team had ripped rebar from the ground, and it stood up in these fantastic, unexpectedly beautiful tangles. There was something organic about it, that pointed to all of the invisible infrastructures that surround and support us, almost like the interior of a body that people work carefully to maintain...

In this country, we have a really strange relationship with the labor that keeps cities running, mail going, water clean, electricity pumping etc. The pandemic highlighted its essential nature. Because I came from a middle-class home but was also exposed to a lot of privilege in the places I was educated, I think I am sensitive to the idea of hard work and hands-on work in service of others — that kind of time-intensive hands-on labor is also part of being an artist. I feel it is a kind of artform.

I also have experience with the hard work of nurses, who were the main interface with my dad when he was sick. All in all, all of this labor that keeps things running — labor of care, even the labor of things like motherhood — is really a labor of love.

We exist in a unique time where this work is going under-recognized and even being punished by our administration, systematically. So this piece may have been one way of addressing that. In terms of the rebar, I love working with construction materials and signage. I find a lot of the items that are utilitarian in Home Depot etc. beautifully designed, and am interested in their evolution and bodily mimicry.

Finally, to process transitions in my life, I turn to poetry. As the pandemic unfolded, I read this letter from Rilke to a friend about love. In terms of the form of the work, I was more interested in ambiguity — versus the many white men on horses with very decisive narratives that pepper Texas — but I was also interested in attentiveness, which is folded into the work you have to do to love yourself, to love other people...

Q: The colors came from Texas sunsets. What happens when you bring something natural into an industrial form?

A: Ah! I am almost always doing this. As humans, we are constantly inventing, and by default, much of these inventions/this design comes from nature. Even rebar is a kind of spine...

My MFA was very intellectually focused, and it was, frankly, a relief to move to Texas for a teaching position because I was introduced to a network of artists that really revelled in visceral things like texture, form, color... things that exist unapologetically, wordlessly, and sensually in nature. For me, the natural world is largely wordless, and does not need to justify itself, so I find a lot of peace and beauty within it. It is a gateway into a more holistic place that enriches my life, and therefore, my studio. I always want to bring that into my work. Back to sunsets: in Texas, you can see very far with the naked eye since it is flat, which leads to incredible views of weather, storms, and in particular — sunsets.

They are routinely stunning with an incredibly rich gradient of every earthly pastel hue — delicious nuances of color and opacity. In a kind of spectrum tandem, there is also a vibrant LGBTQIA+ scene in Texas.

I think the two things came together in this piece, although generally my work shies away from political statements... it was just something organic, that also has to do with the labor of loving each other, which is what all social movements are geared towards — and it is work in this country. The industrial materials reference that work or work in general, but elements of nature point to the body, relationships, longing, intimacy etc... things more murky and shifting that are really at the core of the human experience because they are imperfect and unpredictable.

Q: “Cloud Transmission (to hold and to let go…)” feels light but steady. What pulls you toward things like wind or clouds?

A: Well, likely a combination of both moving and being severely ADHD :) Moving for work frequently means that I have to be light with what I carry, what I choose to hold onto. And being neurodivergent means that my attention is generally anchored sensorially to what is directly in my environment, which I can thankfully channel as an artist most of the time. In this way, I find much of the environment we exist in — offices, social media, computer, etc. — alienating or hard to grasp. In particular, I struggle with the digital element that pervades nearly everything — its ephemerality frustrates me as someone who prefers nature and direct contact, but it also fascinates me. To me it is like a cloud, it evaporates when you turn away from it, but is still very real. In contrast, the ephemerality of nature — of real clouds, or wind, or dew or rain — to me feels spiritual, connected. Being outdoors allows me to unfurl and process different stages of life, like grief, loss, love, connection, longing. The struggle lies in being a human in the 21st century who relies on the precision of CAD design to enact projects.

So those two things came together in this piece. I was able to use the computer, the digital realm to design the work for a huge space, while also thinking about the natural world... at the same time I reflected on the ways in which technology imitates nature and natural impulses.

When you take a photo, you store it in the "cloud"... to hang onto though the moment has passed and no physical token exists. This trend is indicative of a very human desire for stasis, to hold onto things that elude us... time passing, youth, love, memories. We store in the cloud, which I find poetic. When I was making this, I was processing the unexpected death of a loved one, so it seemed particularly prescient. There was also this amazing church group that came to the space and sang and danced, and their energy — the way they came together to process the passage of things in this very emotional way — was woven into the piece. I try to really engage temporality in my work, which is hard, but part of being a person, I think, in general.

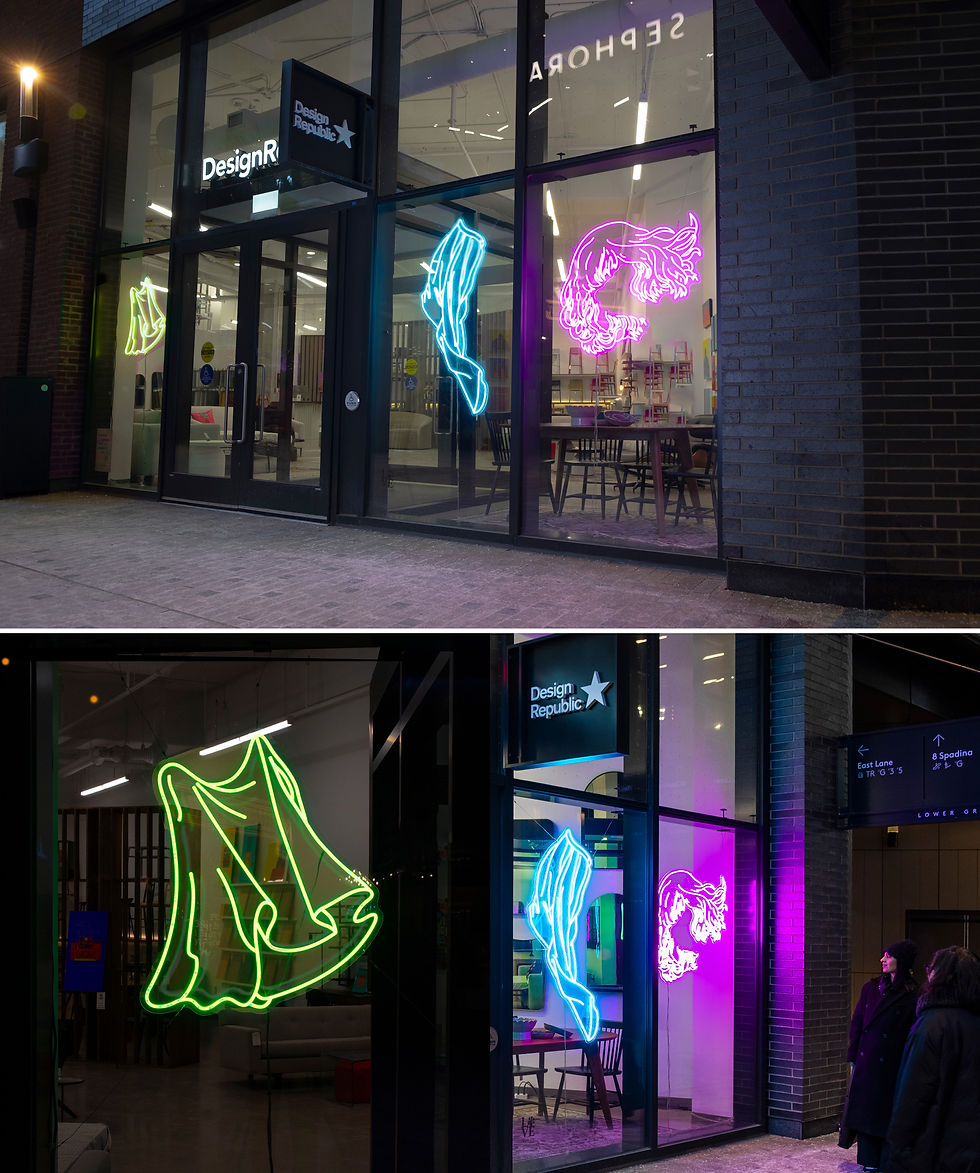

Q: “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress” mixes light, fantasy, and tech. Where do imagination and real life meet in your work?

A: I think my entire studio practice is defined by this meeting, which is something I developed in childhood... as a child who loved realms of fantasy, contained in books and making. As an adult, I am a fairly determined artist, so when I develop an idea (the imagination part), I then have to work on the very practical, real-life aspects of bringing it to life. I work across many media, allowing myself to be drawn to what is new, what best can convey an idea I am having or something I am processing. Because I don't have familiarity with every material, this often means working with craftspeople/industry people who know more about the medium than I do — this is where I step into a role as a designer — which involves meeting people in the real world and learning the practicalities of what can be done.

This particular body of work is heavy on the fantasy side — the forms are borrowed from anime, Disney, and Ukiyo-e shapes (from a database of over 2000 images, traced and altered). The meat of the work is about mystery, and how you can convey it with both line and light. At the time, I was thinking about how the moon, which like nature — is mysterious, elusive, and maybe undervalued. The moon in particular is both fantasy and reality — it is far away and elusive but defines my bodily ebbs and flows in very real ways. I wanted to call attention to this as a working female artist — this beautiful sense of the mystical, of that which cannot be dissected or explained, but is more slippery, more experiential. So I chose forms that are recognizable, hard to pin down, fluid, but also contain stillness and are literally static. The title is another bit of fantasy — after the sci-fi novel The Moon is a Harsh Mistress by Robert Heinlein, where misfits (people eluding category) are sent to the moon to colonize it — as "loonies." I like the idea of embracing the misfit, the uncategorizable but familiar, and celebrating it sensually instead of denigrating it. Outside of my studio, my downtime is spent lapping up stories. I grew up without television for the most part, and so I read everything I could get my hands on, often staying up until 2 a.m. to finish a book even as a child. I love stories and characters. I also love actors and screenwriting, and movies/shows. In a way, I study people and relationships through the medium of my work which I then hope forges a connection with people — a new kind of space to exist in.

Q: You gather language, debris, even mushrooms. How do you know when something wants to become part of a piece?

I know when it looks delicious- I particularly am attracted to the incredible delicacy of tiny things. They seem like a miracle- a mushroom with a cap that is 4 millimeters, moss, dew drops on a spider web, it is amazing to me the natural world. In the US we seem to put emphasis on the loud, or the big, the declarative, the unchanging etc. but to me the really exquisite things are small and quiet, delicate networks that are always subtly evolving.

I also love textures and colors that overlap with industry somehow, alien blobs of a strange mushroom, branches with artificial bends, growths in otherworldly colors.. In general, I collect a lot of things (I always have a plastic bag on me) -- but I don't really know what I will use until I get into my studio and start 'sketching'- combining mushrooms, lichen, moss, plastic items, branches, and medicinal things (needles, pill capsules, syringes, etc) into vignettes that tell stories.

Q: Your work moves between closeness and mass production. What kind of feeling do you want people to leave with?

This is different for me, in different contexts. I think, as a public artist, I am looking to find a space for a kind of resolution... an invitation to somewhere that encourages reflection, contemplation, or letting go... A kind of healing space. Sometimes this can be presenting something so visually delicious it encourages people to turn off the parts of their brain busy planning, naming, predicting, worrying etc. and just observe a thing they cannot categorize but that roots them in their eyes or their body, and from there you can really let yourself go, to be who you are and process things...

With other work, sculptures and installations in more gallery-type settings (like the 'tree series' on my website), the emotions are more ambiguous, more reflective of my own ambivalence about this world, the seductive and unsettling aspects of the technologies and methods of production that pervade our lives now. For example, where do we draw the line with technology? We now have AI that may replace human labor, even the labor of emotional relating... is this good or bad? It is attractive and easy in some way, but I frankly find it alienating too.

What happens when we spend more time on our phone than with people? Viewed another way, we are not more 'connected' - but at what cost? I think my work that goes in galleries speaks to this unease, but also its inevitability (the merging of technology, humanity, and the natural world...). For me, in this work (gallery work, versus public installation), there are no real conclusions. This is, in part, because I have visited and worked in countries with little technological infrastructure, and this is also not ideal- the lack of industry puts people's live at risk.

Mass production is odd because we have this close daily interaction with things whose origins are mysterious, made by bodies and machines alien to us. This is all very weird - I think of it as 'structured alienation', a condition we kind of just have to accept in many ways, and exist around. In this way, love, the labor of love, the work that goes into connecting, is the antidote. So maybe this is why I make things.

So in a way, technology IS like nature... it is a beautiful, ambiguous, constantly evolving network that gives... but also takes. That being said, I think we need a more level headed approach to technological development that takes into account the future of humanity on earth. I do not always have faith we will do this - so in a way my work is seductively dystopian, but rooted in human relating. It addresses the gap between desire and resolution, between longing and stillness - which is embedded in the entanglement of nature and tech, but also just the human condition.