Giulio Zanet

- Anna Lilli Garai

- Aug 12

- 5 min read

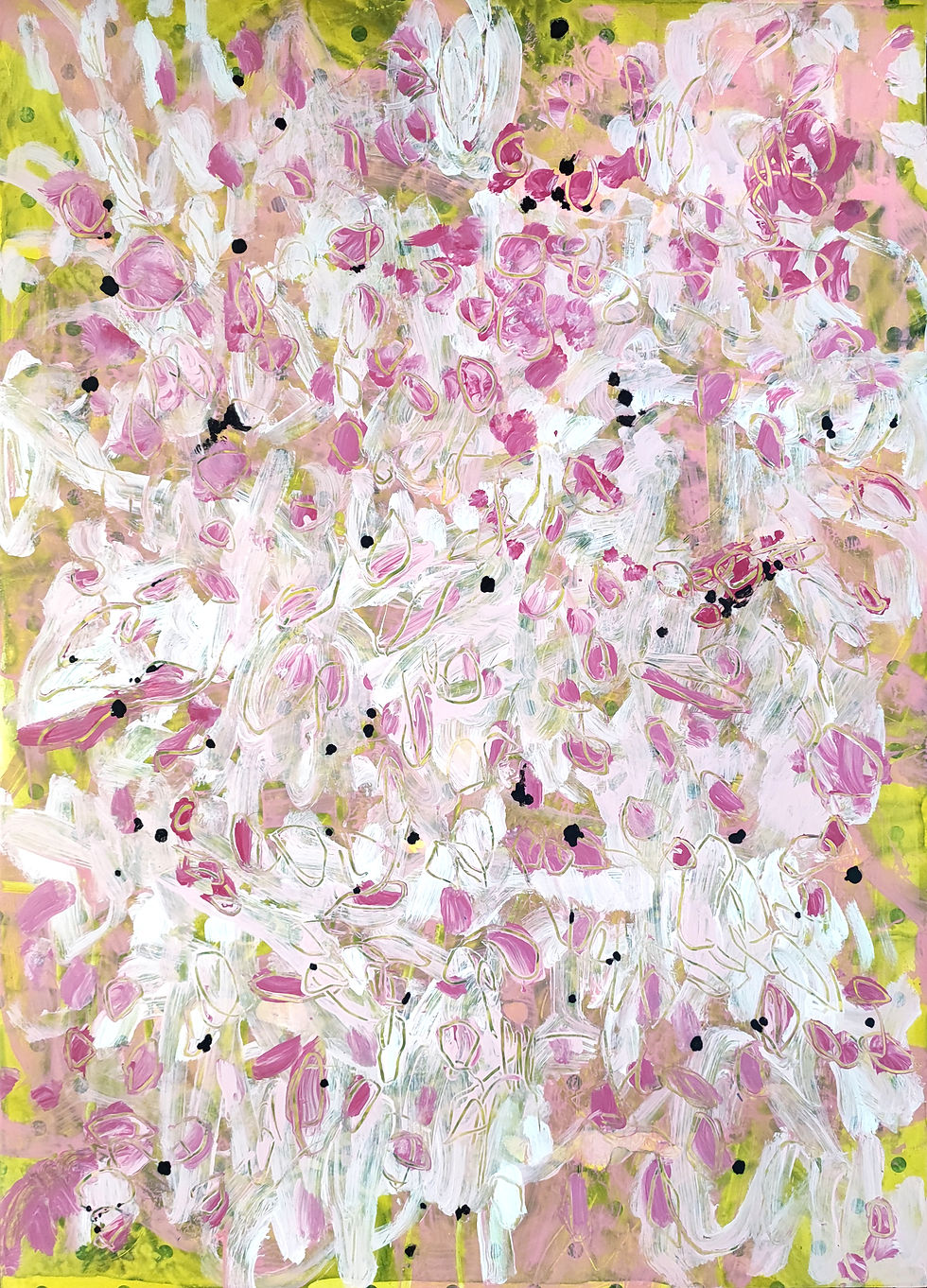

Giulio Zanet is an Italian painter whose work centers on abstraction, gesture, and the unpredictability of image-making. He often starts without a fixed idea, letting the surface guide him through repetition, omission, and ambiguity. For him, painting is a way to explore fragility, silence, and the invisible layers of emotion. Working in Correggio, far from the noise of the city, he approaches the canvas with patience, building each piece slowly and intuitively. His practice reflects a personal rhythm and an openness to not knowing where a work will lead.

Q: You describe painting as a metaphor for a constant search for loss. When did this feeling first become part of your way of working?

A: I see painting as a constant search for loss, but not in a negative sense. It's more about a deliberate surrender of control, a giving in and following my own nature. This attitude gradually matured within me, becoming more central as I moved towards abstraction. Like many artists, I had a long figurative period. That phase paradoxically taught me how to 'lose myself' within the image itself, going beyond its literal representation. Today, when I stand before the canvas, I never have a precise direction or a predefined final result in mind. Instead, I let myself be guided by the painting itself: by the colors meeting, by the gestures following one another, by the textures emerging. In this sense, loss is a sweet wandering over the surface, much like the idea of roaming through an unknown city without a map, intentionally getting lost to discover unexpected corners and perspectives. Every layer, every mark, is a step in this creative disorientation that always leads to something unpredictable and authentic.

Q: Movement, embarrassment, and a quiet humor run through your abstractions. What draws you to these fragile emotional states?

A: These emotional states – the inner movement, that subtle veil of embarrassment, a quiet, almost melancholic humor – attract me precisely because I believe they are universal, intrinsic to every human being. There's no human experience untouched by these nuances. My interest lies in listening to them, perceiving their vibrations, and trying in some way to translate them into painting. It's not about literally illustrating them, but about finding a visual language, made of forms, colors, and gestures, that can evoke the same emotional resonance in the observer. It's a way to explore the fragility that distinguishes us, to show that even in the absence of recognizable figures, painting can speak directly to our deepest emotions. I try to capture the essence of these sensations, making them visible through the non-visible.

Q: Your work avoids familiar forms. Do you ever feel tempted by figuration, or is absence the point?

A: Yes, as I mentioned, I come from an initially figurative background. But over time, the figure began to dissolve, to disappear, leaving space exclusively for pure forms and color. For the past ten years, figuration not only no longer attracts me, but I actively try to move as far away as possible from any recognizable form. It's true that the human eye has an innate tendency to seek patterns and familiarity, to find something to cling to; my challenge is precisely to resist this tendency, to shift direction towards the non-recognizable. So, at this moment, I can definitively say that the absence of figuration is the focal point of my work. It is in that absence that a space of interpretive freedom opens up, a more direct and unconstrained dialogue with the observer, one that is not bound to a predetermined meaning. However, art is a journey of continuous evolution, and I cannot rule out that figuration might return in the future, perhaps in new guises or with a completely renewed and different meaning from its initial one.

Q: Ambiguity, repetition, omission—these elements seem to structure your language. How do you decide what stays and what falls away?

A: This is one of the most difficult questions to answer, because the decision isn't rational, and I don't exactly know it myself.

I know for sure that ambiguity, repetition, and omission are intrinsic to my practice, almost like automatic responses that naturally emerge in the creative process. Every time I start a new piece, I find myself grappling with them. In reality, I yield a lot to what happens on the surface as I work. There's no predefined plan or clear idea of what should emerge. It's a constant dialogue between me and the canvas: sometimes a mark proves more powerful through its repetition, other times the omission of a detail creates a greater impact, or ambiguity allows for a richer, deeper interpretation. The decision of what remains and what vanishes is often dictated by the moment, by the feeling the work begins to evoke in me. And perhaps the most complex question of all is precisely when a work is truly finished: it's an intuitive moment when I feel the canvas has achieved its own autonomy, its own complete expression, even while retaining its inherent imperfection.

Q: You talk about painting as a survey on representation. What questions are you asking yourself when you're working?

A: Yes, painting for me is a continuous investigation into representation, or rather, its absence. One of the most persistent questions I ask myself while working is the great dilemma of "why create new images" in a world that is already saturated, even besieged, by an incessant flow of images. I mean that very often images are conceived to represent something specific, to convey an immediate message, or to faithfully reproduce reality.

I, on the other hand, try precisely not to represent anything recognizable.

In this sense, my painting investigates how much an image can exist while not explicitly representing. Or, paradoxically, how an image that doesn't illustrate anything specific can at the same time represent innumerable things to the viewer.

It's a search for abstraction's inherent ability to open up to infinite interpretations, to become a mirror for the projections, sensations, and thoughts of the viewer, rather than merely a vehicle for information or a window onto the visible world.

Q: You live between Milan and Correggio. How do these two places influence your rhythm or mindset in the studio?

A: Actually, for a few years now, I've been living and working exclusively here in Correggio. This life choice profoundly and singularly defines my rhythm and mindset in the studio. I lived in Milan for fifteen years, and that period undoubtedly shaped a part of my journey, but the move here, which happened for love, radically redefined my approach. Away from the ferment and distraction of big cities, Correggio offers me an environment of calm and quiet essential for my artistic practice. Here, time seems to expand. There are no interruptions or the frantic pace typical of urban environments. This allows me to dedicate long hours to pictorial meditation, to a total and uninterrupted immersion in the creative process. It's a place where I can truly allow myself to "get lost" in painting, to patiently build layers, to listen to the materials and forms that emerge on the canvas without rushing. The particular light of these areas, the silence, and even the muffled sounds of the province contribute to a deeply introspective mindset.

This secluded environment allows me to fully concentrate on that intimate dialogue between me and the work, which is fundamental to my process. Correggio is not just a physical place for me; it has become a true mental condition: a refuge that nourishes my search for depth, for inner silence, and my curiosity towards what is not immediately visible, towards the essence of things.