Claudine Hauke

- Anna Lilli Garai

- Jun 25, 2025

- 4 min read

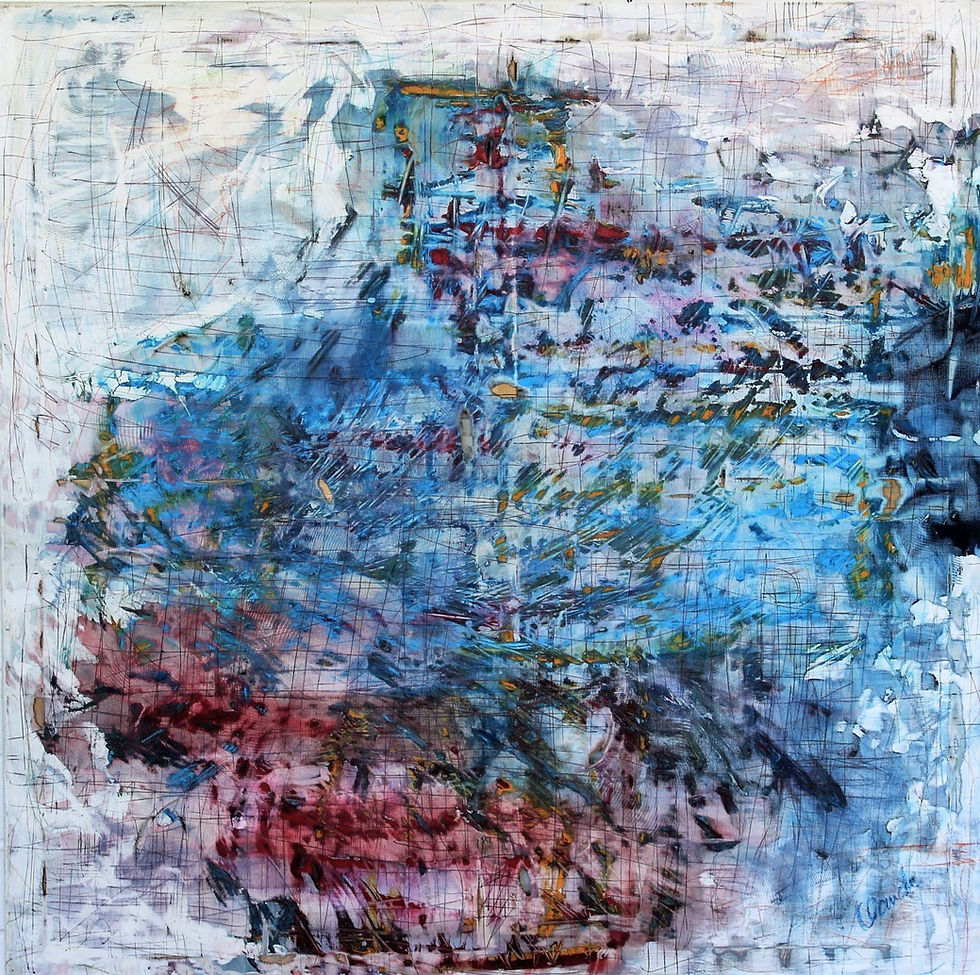

Claudine Hauke works across painting, textiles, and mixed media, often combining oil, thread, and fabric in tactile, layered compositions. Her practice is grounded in a physical, process-based approach that involves building and breaking down surfaces—scraping, sanding, stitching, and tearing—to reveal what lies beneath. Her visual language is marked by bold colors, scribbles, and strong brushwork, shaped by lived experiences and the pressures of contemporary life. Many of her recent works reflect on education, displacement, and personal loss, using visual tension and material contrast to explore memory, repair, and transformation.

Q: When you're sanding or tearing into a painting, what kind of emotion or impulse usually leads the way?

A: The act of sanding a painting often comes from a place of emotional unrest—times when I’ve felt unhappy or distressed. There’s something deeply cathartic about the process. Using the machine, which is incredibly powerful, I methodically work through each layer of oil paint. As the surface transforms, a new piece gradually reveals itself. It reminds me of the way the human body changes over time—eroded, reshaped, and redefined by experience. It's a kind of rebirth. What’s most fascinating is the unpredictability; I never fully know what will emerge. Each piece surprises me, as if it's uncovering something I wasn’t consciously aware of when I first painted it.

Q: Stitching shows up in several works. When did it start feeling like more than just a material choice?

A: At first, stitching appeared sporadically in my work—almost like another mark-making tool rather than something deeply intentional. But after the passing of my husband, when I returned to the studio last year, it took on a different weight. Without consciously planning it, I found myself using stitching more extensively. It became a way of piecing things back together—not just the canvas, but my life. Over time, it evolved into a symbol of connection, of building and holding things in place. It moved beyond technique and became something deeply personal—a gesture of healing and reconstruction.

Q: You’ve described your process as erosion and exposure. Do you think about what you’re revealing—or just what’s left behind?

A: When I’m working, the process is largely intuitive—I don’t go into it with a fixed idea of what I want to achieve. But if I had to choose, I’d say I’m more drawn to what is being revealed. There’s a thrill in watching something unexpected emerge from beneath the surface.

That moment of revelation—of uncovering what was hidden—is far more compelling to me than what gets left behind. It feels alive, as if the work is showing me something I didn’t know was there.

Q: "Outreach Under Pressure" feels deeply personal. How did grief change the way you approached scale and composition?

A: Grief has a way of distorting everything—time, space, even the body. When I began working on "Outreach Under Pressure," I found myself instinctively shifting the scale. The works became larger, more physical, almost confrontational. I needed the space to carry the weight of what I couldn’t express in words.

Compositionally, things became looser, more fragmented. There was less concern for order and more for honesty. Grief stripped away any need for perfection—it allowed rawness to take up space. The process became less about controlling the work and more about letting it hold what I was going through.

Q: Your work often speaks to social disconnection and survival. How do those ideas shape your daily practice?

A: Over the past 24 years, I’ve lived in four countries—ranging from bustling cities to remote villages—and now I find myself in a small seaside village in South Africa. Across all these places, one thing has remained constant: a deep sense of social disconnection. It’s often subtle, unspoken—people struggling without fully understanding why.

This awareness has shaped not just my artwork, but how I live and work. Earlier this year, I opened a small gallery space in my home. We host talks, art dinners, and I’m in the process of developing an art garden on the property. My aim is to create a space that fosters connection, reflection, and conversation.

In my studio practice, I try to be as open as possible. I allow my emotions to surface and become visible in the work—but I also leave space for the viewer. I want people to see something of themselves in the pieces, to feel less alone. Art, to me, is a bridge. It can connect us to each other, to our inner lives, and to the world around us. That belief guides everything I do.

Q: When a piece feels finished, is it more about the image or the physical memory built into the surface?

A: It's both, but perhaps more about the physical memory—the accumulation of gestures, layers, and decisions embedded in the surface. When I paint, I’m not only working through emotions and questions; I’m also building a physical record of that internal process. Every mark, erasure, or added texture holds a trace of that moment. The surface becomes a kind of skin—scarred, layered, fragile, and resilient all at once.

A piece feels finished when I sense that I’ve said what needed to be said through the material. The image might be raw or unresolved visually, but if it mirrors the truth of that moment—emotionally and physically—then it’s complete. For me, painting is a dialogue between thought and touch, presence and absence. The work is done not when it’s perfect, but when it stops asking for more.