Chris Shaw Hughes

- Anna Lilli Garai

- Jun 25, 2025

- 5 min read

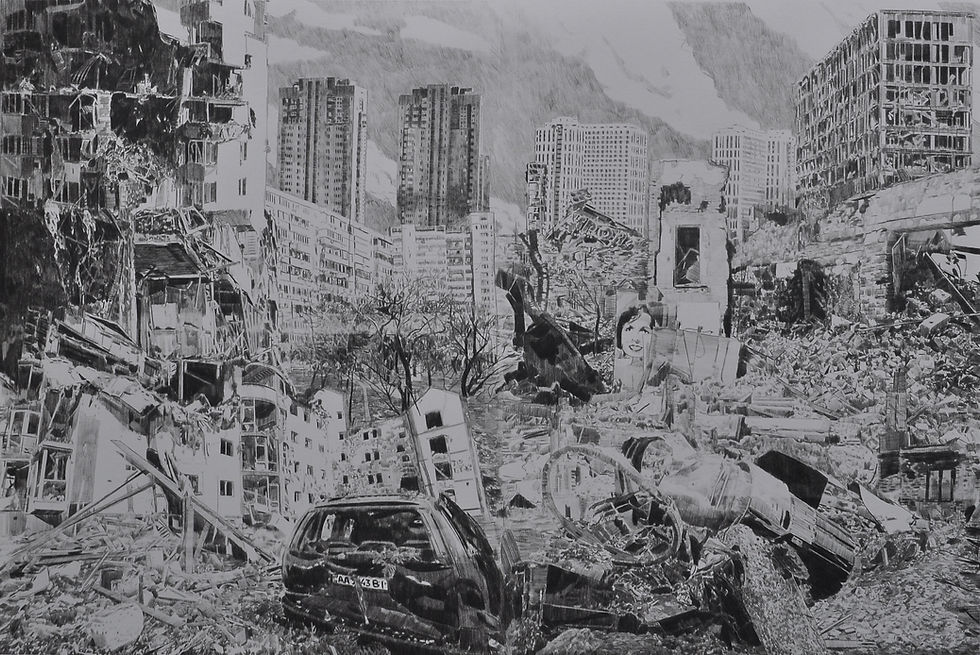

Chris Shaw Hughes focuses on how places become marked by conflict and mass media imagery. His ongoing body of work draws from historical and recent photographs of bombed cities, tracing how civilian spaces are transformed during war. Using carbon paper as his main medium, he recreates these images through a slow, detailed process he calls Traumatic Realism. His background in advertising shaped a concise, image-led approach that contrasts with the heavy subjects he addresses. The resulting drawings invite reflection on the quiet presence of trauma in everyday visuals.

Q: What first drew you to sites of trauma as a subject? Was there a specific moment or image that stayed with you?

A: It was probably 9/11, and the fallout of the “War on Terror.” Something that struck me was the American re-appropriation of the term “Ground Zero,” which had originally been used to name the point above Hiroshima where the first atom bomb used against people was detonated. It felt like someone was trying to say that these two events were in some way the same or equal. Yet one was seen as the “crime of the century,” and the other as a necessary act of war.

The real crime was that they were both horrific examples of the practice of targeting civilian populations during war and conflict, and I set out to research as many examples of where this had happened before. I created a series of works showing as many places as possible where civilian populations had been targeted by mass bombing. It’s a very large series.

Q: Why does carbon paper feel right for this work? What does it add to the way you process these images?

A: The first ever drawing that I made using carbon paper was of the site of the destroyed Twin Towers, which I made from a wonderful aerial photograph in The Guardian showing the process to clear the site and start rebuilding it as a memorial.

It was incredibly detailed, and the only way I felt able to properly represent it accurately was to use carbon paper.

The use of this deep black material, which also produced a hand-made negative as well as the drawing, allowed me to investigate the use of a negative aesthetic. That seemed more appropriate when working with subjects of a traumatic, repressed, or taboo nature.

Adorno once said something like, “After the Holocaust there can be no poetry,” which was akin to saying artists should not use events such as these to make art. However, artists cannot stand by and say nothing when terrible things happen, so I feel it is important that we bear witness and speak out for those who have no voice.

People see photographic images like these every day on the internet, the TV news, and in the press. By making drawings of them, I’m slowing down the viewing process. Hopefully people don’t just swipe right or walk by, but may ask why I have made the drawing.

Q: How do you choose which events or places to focus on in your series?

A: Finding the right kind of images is the hardest part of my process. I refer to the actual drawing part as colouring-in because most of the work has been done prior to the drawing.

At the start, I used World War II images from archives, magazines, and books. There are many images of destroyed German cities because the Allied bombing was so successful. The images have to be as high-res as possible, with a kind of three-quarter aerial viewpoint to get the depth, and relevant to the theme.

I feel that I earn the right to use these photographic images by spending more time with them than anyone ever has.

I then moved on—as the world moved on—and started looking for more contemporary images where exactly the same targeting was happening. For all the advancements in military hardware (and software), smart bombs, drones, and computer-guided missiles, the civilian always ended up being the main casualty.

So as the Middle East became more of a focus for conflict, so did my drawings.

Q: You use the term Traumatic Realism. How has that approach evolved for you over time?

A: I was trying to find an appropriate name for what I was doing. Then I saw a book by Michael Rothberg called “Traumatic Realism: The Demands of Holocaust Representation,” where he looks at the question of “how to comprehend the Holocaust and its relationship to contemporary culture” and the function of using realism in representing traumatic events.

I don’t make work about the Holocaust, but by its omission my work also brings it to bear. The question may be asked: “You make work about sites of trauma, why not that?” The question is asked so the trauma is visible. The phrase—and the question—is as relevant today as it ever was.

Q: How has your experience in advertising shaped the way you work with visual language now?

A: I guess it gave me a critical eye and a cynical edge. I fell out of love with advertising as I grew older and witnessed the techniques used to sell things. Don Draper in Mad Men says something like, “Advertising is about selling one thing… happiness.”

I don’t think that’s true. I think it’s selling dissatisfaction: “If you don’t buy these nappies, you’re a bad mother.” “You’re not good enough, so you need this spot cream, deodorant, anti-aging skin cream, or hair shampoo.”

It’s a terrible industry, really. But I digress.

In the beginning, I always thought that I was making art—using illustration, photography, words, etc.—to make something that looked great and maybe sold a few JCB diggers, low carbohydrate beers, or mortgages.

I also learned brevity—less is more, so to speak—so my work is not flamboyant or particularly stylish. It’s reduced down to its bare essentials.

To quote an old ad campaign, my work “does what it says on the tin” and shows, very literally, the aftermath of war and conflict.

Q: When working with large-scale destruction, how do you keep the human presence at the center?

A: The simple answer would be that I don’t. In many of the earlier World War II drawings, there are no—or very few—people in the images. However, as I said earlier about the Holocaust, their omission speaks as loudly as if they were there.

You see empty streets and ask, “Where are the people?” Like Doris Salcedo’s empty domestic tables or cement-filled wardrobes, chairs, and beds—which speak loudly of the absence of people that used to use them—those early drawings shout out the fact that the people are gone.

The later drawings from the Middle East have more people in them, and I think this speaks to how common these scenes are now. Within hours—or even minutes—of an airstrike or bombing, people are back on the streets. It’s almost as if it’s normal for them. Life must go on.